Narrative Manipulation: Ancient Practice; Modern Means

Narrative Intelligence Part I

Days before the 2024 New Hampshire Democratic Primary, some voters received a robocall from one of the candidates. It seemed like a typical political robocall: mildly irritating, but innocuous. Only this time, there were a couple of things wrong. First, it called for people to vote on the wrong day. Second, it wasn’t the candidate who recorded the message, even though it was his voice. In fact, supporters of a rival candidate spent just a few hundred dollars to record this “deepfake.”

AI is bringing us into a new era of manipulation of the world around us. How do we know what is real and manipulated? Misinformation, fake news, propaganda, disinformation, rumors- all AI-generated and very realistic, seemingly threaten to overwhelm us.

Yet while the terms may be relatively new, the concept of intentionally or unintentionally manipulating the media or information environment- narrative manipulation- is nothing new. In fact, society has been confronted with this issue for quite some time.

Narrative Manipulation is willfully or mistakenly spread false or misleading stories about the world. It encompasses terms like misinformation, disinformation, propaganda, fake news, and many more.

Let’s look at a couple of examples:

Through the Ages…

- In Classical Greece, like today, a major part of the battlefield of the Peloponnesian and Persian wars were fought in public assemblies, democracies, and discourse.

- The casus belli of the Spanish American War was a manufactured controversy over the sinking of the USS Maine.

- During World War I, the British government employed propaganda techniques to exaggerate German war crimes in Belgium and elsewhere, fostering anti-German sentiment among neutral countries and their own population to boost enlistment rates and support for the war effort.

- Throughout the Cold War, the KGB's Operation INFEKTION in the 1980s, spread the false claim that the U.S. had invented HIV/AIDS as a weapon.

- North Vietnam’s effective portrayal of the Tet Offensive as a success- even though it failed at all of its objectives and decimated the South Vietnamese Communist apparatus- was a turning point in the war.

- The Rwandan Genocide in 1994 was fueled by radio stations and newspapers which spread false accusations, rumors, and propaganda against the Tutsi minority, leading to the rapid escalation of violence.

Let’s unpack a couple of these examples…

Thucydides & Herodotus[1]

“For where it is necessary that a lie be spoken, let it be spoken.[2]” - Thucydides

The earliest historians of the Classical Greek world- Thucydides & Herodotus- were attuned to narrative manipulation[3]. Both record politicians and leaders manipulating facts in their discourse to achieve their goals, despite cultural taboos against doing so. We see this take several forms.

In some cases, leaders manipulate the nobility to go along with a course of action. They use oratory and rhetoric to weave facts and fictions into a seamless narrative: effective disinformation.

Likewise, rumors spread intentionally by political factions played a large role in the public. The Athenian tyrant Peisistratos orchestrated a disinformation and rumor campaign in the masses to overthrow the existing government. He even used a deep fake of a deity to get the message across[4]! Oftentimes, these events of narrative manipulation are played out in public assemblies, through timely heralds spreading false information, or otherwise.

Were Greek societies helpless in the face of these threats? Hardly. Both democracies and oligarchies developed mechanisms to overcome narrative manipulation, and thrive, though they weren’t always successful.

- They used assemblies to ensure the city leadership were getting the best possible information.

- They established the intent of the messenger, the content of the news, and considered the implications.

- They cross-examined witnesses, and sometimes sent their own trusted messengers to gather information for themselves.

- Leaders used oratory to combat propaganda, and trustworthy messengers reported back on the facts, (the first marathon)[5].

These tools were effective in these days, particularly when decision-makers were highly concentrated and human voice and the written word were limited in reach.

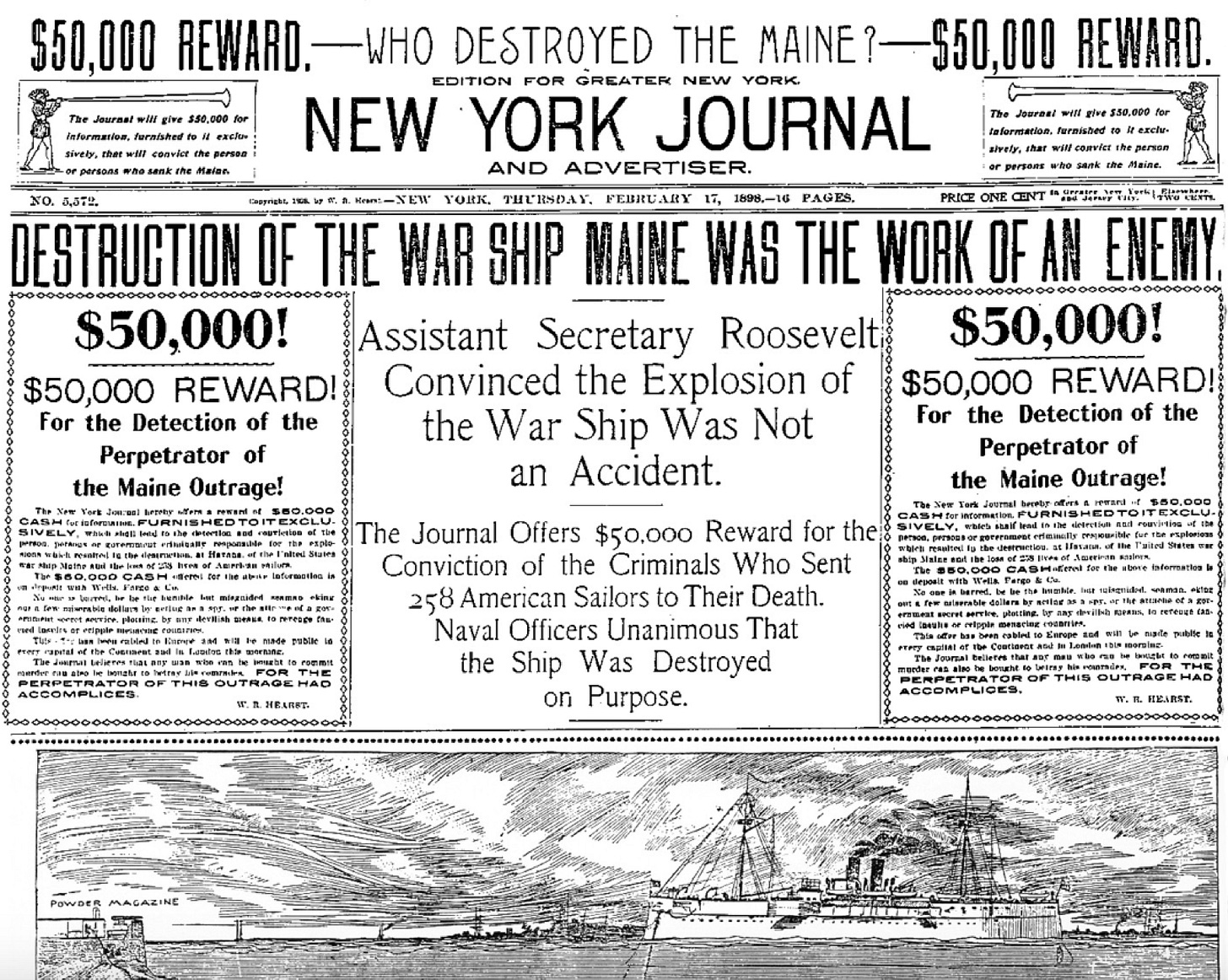

“Remember the Maine!”

An example of narrative manipulation in US history was the explosion of the USS Maine in Havana Harbor. Prominent newspapers- in particular ones owned by the Hearst and Pulitzer companies, were strident in laying full blame for the tragedy on the Spanish authorities. Public pressure led to nearly the whole crew being awarded Medals of Honor by Congress, and soon thereafter a declaration of war. Additionally, newspaper accounts of Spanish brutality towards Cuban freedom fighters were accentuated, as were attacks on American citizens. While the US fought the war, public support quickly weakened as the costs became clear and the hype faded away. After the war, some changes:

- Consumers started seeking out a wider variety of sources in their news.

- Newspapers started striving for neutrality, with many fits and starts.

- Now, the name “Pulitzer” is synonymous with the journalism prize for accurate and vivid reporting, not jingoism.

Today

While we could discuss numerous other eras of history, the point stands that well-functioning societies develop tools, policies, and practices to overcome narrative manipulation. Whether the specific threat is manipulation by foreign actors, untrustworthy or co-opted media outlets, or from technological tools like artificial intelligence and deep fakes, most of the tools to combat these threats already exist.

- Fight Narrative Manipulation with Narrative Intelligence. Develop a comprehensive understanding of the source before trusting the narrative.

- See a variety of perspectives. Censorship doesn’t work, and most narratives contain at least some of the facts. A clearly biased source may be reliable in some respects.

- Verify the facts first, then see how the narrative accounts for them. The same source can be spot on sometimes, and wildly off on others.

- Be proactive in getting your message across, and the facts. The longer it takes to confront narrative manipulation, the more entrenched it becomes.

- The more polarizing an issue is, the more incentive there is to use narrative manipulation.

Conclusion

Narrative manipulation is a tool as old as human communication. The addition of AI presents a major threat, but humanity has or will develop the tools- narrative intelligence- to get to the bottom of things. At Fairwater, we’ve been thinking deeply about how to tackle this problem in today’s age. This is the first in a three part series.

[1] Lateiner, Donald. "“Bad News” in Herodotos and Thoukydides: misinformation, disinformation, and propaganda " Journal of Ancient History, vol. 9, no. 1, 2021, pp. 53-99. https://doi-org.proxy.library.upenn.edu/10.1515/jah-2020-0005

[2] Herodotus Histories 3.72.4

[3] Leaving aside that Thucydides’ stated purpose for the book was correcting the previous narrative of the Peloponnesian War..

[4] Herodotus Histories 1.60.5

[5] Ibid; book 6.